Once upon a time, long long ago, more than 500 of us studied an intensive course on a residential campus — in the midst of lush greenery and Nagarbhavi’s growing social scene, surrounded by the smell of strong Chetta coffee, constant banter, omnipresent PDA and several snakes. And then COVID-19 happened. The End.

Just kidding! Soon after the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic by the WHO, the Karnataka government issued orders on 13 March 2020 for the closure of universities. Over the weekend most of us left for home, with a heavy heart, but also with hopes of returning within this trimester (confidently packing a grand total of 5 t-shirts  ). The administration promptly and fairly efficiently resumed classes on 18 March 2020. Having largely stuck to the academic calendar and with no disruption to classes, we’re almost at the end of this trimester. Our projects have been submitted, the last set of vivas is scheduled for the next weekend, and exams are just around the corner (albeit with the guidelines having shocked us all). All is good.

). The administration promptly and fairly efficiently resumed classes on 18 March 2020. Having largely stuck to the academic calendar and with no disruption to classes, we’re almost at the end of this trimester. Our projects have been submitted, the last set of vivas is scheduled for the next weekend, and exams are just around the corner (albeit with the guidelines having shocked us all). All is good.

H a h a h a

All is not good.

COVID-19 has been extremely dangerous, not only in terms of its physical health risks and mortality rate, but also because it has battered the economy and induced, possibly, the worst mental health crisis ever on a global level.[1] Many countries do not have adequate mental health infrastructure and even if they do, it is not accessible to all sections of the population. Around 300 deaths in the lockdown period in India were non-COVID-19 deaths, related to deteriorating mental health.[2] And this was just the figure around the beginning of May. One can only speculate how much worse this is going to get, propelled by rising unemployment, an increase in health issues, recession, anxiety about future prospects, etc.

‘No man is an island.’ Apparently, neither is Law School.

Several colleges have taken many pro-active steps to support students coping with academic pressure as well as the other problems they might have at home, and also to remedy inequitable access to online resources. At NLS, various stakeholders have been at loggerheads on how to approach online learning and adapt schedules and rules to these trying times.

To get a more “objective” insight into how all of us at NLS are doing, as well as for all those living in denial/under the assumption that students exist to lie/scam/cheat by feigning problems, Quirk sent out this survey to the student body on 10 May 2020. We received 130 responses to our survey, which amounts to roughly 25% of the student body. These responses were fairly evenly distributed across all batches.

76% of the respondents said that their work and academics were being affected due to several COVID-19 lockdown related reasons. This is an overwhelmingly large fraction, and it is quite alarming that students have to continue to push through this trimester – almost as if things were as usual – knowing that their academic performance is going to take a hit one way or the other. As one respondent put it, “cognitive skills have tanked like the economy”. Students’ university work has been adversely affected by (i) lack of empathy from college, (ii) worrying about people they know, (iii) financial trouble, (iv) social media, connectivity and network issues, and (v) stress on account of staying at/being unable to stay at home.

These issues have also manifested in many other ways – such as, procrastination, change in sleep schedules, and becoming more closed off.

Procrastination, often seen as a sign of laziness, can signal a drop in the productivity of students because of them being mentally unable to push themselves to work. 71.8% of respondents felt that they were procrastinating more than usual. We’re not always the most efficient cogs of a machine even when in college (which Chetta and Netflix can confirm), but efficiency levels have significantly worsened now, adding to guilt and worries regarding academic performance. There have also been very ableist messages going around during the pandemic, urging people to be banana-bread-baking-new-language-learning-webinar-viewing-high-functioning individuals, which only induces additional pressures. However, there are several factors which could account for people experiencing a drop in productivity, and leading to procrastination.

Some unique reasons cited by respondents included the summer bringing in a lot of seasonal work in rural areas, suffering from a chronic illness, and feeling like “nothing matters anymore so what’s the point of doing anything”. One respondent also said, “I feel very very discharged – I’m not someone who talks to people much, but I derive a lot of energy and strength from just sitting with people, even if I’m not actively participating.”

The mental strain has also contributed to changing sleep cycles, with 78% experiencing some degree of change and 10% of respondents saying they now have no regular sleep cycle at all.

Adapting to Atmanirbhar: The Newest Trend on the Block

80% of the respondents are not currently seeing a mental health professional, but about 25% of them said that might consider seeing one in the near future. Unfortunately, of the 20% who were seeing a mental health professional, a large majority (85%) are no longer able to do so under lockdown. While the college counsellors remain available remotely (albeit, in one case, taking weeks to respond to a student’s mail), there clearly remains a barrier to access which is disappointing, especially given the additional mental toll under lockdown.

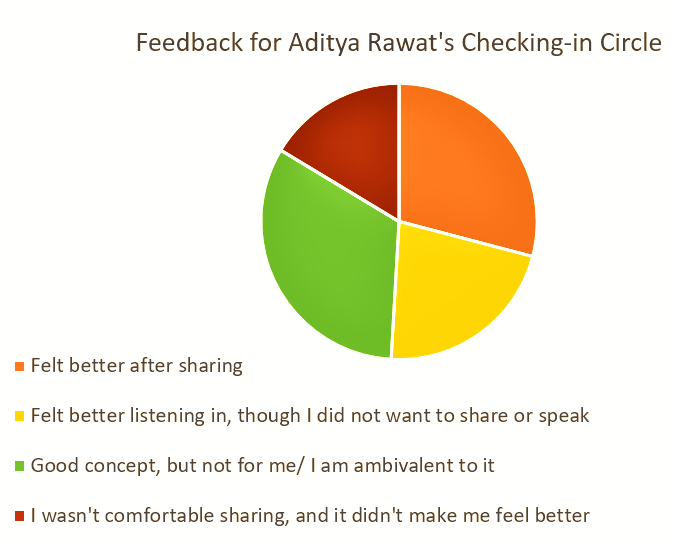

We’ve also had peer group mental health sessions, organised by Aditya Rawat (Batch of 2022). While he’s had this idea for a while, the lockdown gave him the push to hold the first session on 28 April. He has moderated a few sessions of the ‘Check-in Circle’, open to all students, where students are free to share how they’re doing or just lend an ear and some support for others. Although only 20% of the respondents had attended the Check-In Circle, almost all of them (92%) had a positive or neutral experience.

When we asked Rawat what he thinks of the sessions and whether they take a toll on his mental health, he said that while it could be exhausting at times, it helped that “the participants were also active listeners, who hear out whatever it is I want to share. Also, all those who have joined us for these sessions so far, have been very supportive and understanding which helps ease whatever pressure there is supposed to be on me as the moderator” and that he looks forward to seeing more of us join the next session!

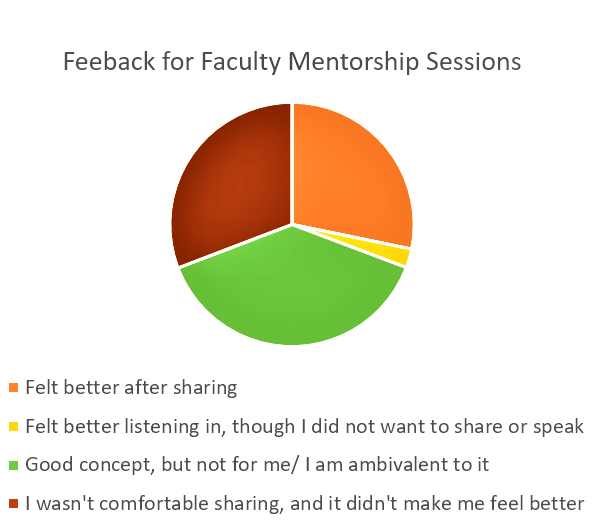

The Faculty Mentorship Sessions (which started this month and of which, only one session has been conducted so far) saw a slightly higher rate of attendance (29%), with 68% having a positive or neutral experience.

Several factors influence the rate of attendance: some students had not been allotted a Faculty Mentor or their Faculty Mentor had not conducted a session at the time of the survey, and some students may have chosen to attend/not attend based on which Faculty Member was assigned to be their mentor. The feedback was fairly diverse — some students didn’t feel comfortable sharing their problems with their Faculty Mentor, while some students felt like their session was well conducted by the Faculty Mentor. Most agreed that the discussions revolved around academic pressures, especially the forthcoming exams.

So, umm, what was the point of all this?

Well, primarily to check up on everyone and remind everyone to take care of their mental health in these tough times! We also wanted to collect tangible objective data to chronicle the effect of the lockdown and emphasize the need for better mental health infrastructure (and some sympathy for starters!).

From the rant column provided at the end of the survey, we came across at least one very grave mental health issue, which the person attributed to the apathy they faced from the university administration. On the other hand, one person mentioned that they were coping well, had higher productivity, and felt that the survey form was too negative (who are you and what are your ways?!).

Before you conclude that this survey was just a sob fest, we also asked how much people missed their friends and Law School, on a scale of 1-5. While over half the respondents seemed to miss both, almost one-fifth said they don’t miss Law School at all! But the general feeling towards this was perhaps summed up best by a respondent who asked, “Is there even any difference between these two questions?”

So, until we meet next, take care of your mental health, remember you’re not alone, and know that Law School misses you back!

Godspeed,

Jwalika and Smriti

PS: Quirk’s always here in case you want to share your rant!

[1] ‘Major Mental Health Crisis Looming From Coronavirus Pandemic: UN’ (NDTV.com) <https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/coronavirus-un-secretary-general-antonio-guterres-says-major-mental-health-crisis-looming-from-coronavirus-pandemic-2228460> accessed 23 May 2020.

[2] ‘Suicide Leading Cause for over 300 Lockdown Deaths in India, Says Study’ The Economic Times (5 May 2020) <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/suicide-leading-cause-for-over-300-lockdown-deaths-in-india-says-study/articleshow/75519279.cms?from=mdr> accessed 23 May 2020.

]]>For those who don’t know me, I shall give a brief introduction. My name is Megha Mehta. I had gained a considerable amount of fame at NLS for my summaries (which I think are still in circulation) and in later stages of law school life, for my movie reviews. I may also have acquired infamy for other reasons, but for that, you’ll have to wait for my full-fledged autobiography to be released 30 years later.

Without further ado or clichéd platitudes on Corona Pyaar Hai, I will jump to the aim and objective of my article, laa-school project style. I am currently clerking with Hon’ble Justice M.M. Shantanagoudar at the Supreme Court. I have written this piece to illuminate my fellow law school brethren about the potentialities of working as a law clerk for a Supreme Court judge post-graduation. Through this article, I wish to answer certain FAQs such as what is a clerkship, what are the responsibilities of a clerk, what is the learning experience like, how do you get a clerkship, is it true that the Supreme Court is run by the Illuminati, etc.

With regard to scope and limitations, I have deliberately refrained from commenting about my personal clerkship experience because I wanted this to be a general primer on clerkships and not a recruitment ad for my office specifically, though I have mentioned it briefly at the end of this piece. Also, I am continuing for a second year so that’s a separate piece which I will presumably write once my clerkship officially ends. Instead, this article is mostly based on an amalgamation of what I’ve seen and heard across various Chambers. It may not be possible for this piece to answer all queries, and some information has been kept vague on account of confidentiality requirements (particularly the Illuminati question). However, I hope this can give you a fair idea of what a clerkship truly entails.

What is a clerkship? What kind of work do you do?

A law clerk is basically a research assistant to a judge. The bulk of my work as a law clerk involves doing what I have already done for 5 years in law school — making ‘briefs’ of the case files which are listed for admission before Sir. Though the format of ‘briefs’ and whether a judge wants written or oral briefings differs from office to office, the contents of briefs are usually similar. They include the facts of the case, the case history from the trial court to the SC, and most importantly, the ‘grounds’ on which the case merits consideration by the Court. Apart from this, I also attend court and make briefs of arguments made during regular case hearings, and assist in preparing research notes for judgments and Sir’s public speaking engagements.

At the outset, I find it necessary to point out for the uninitiated that a clerkship is not strictly a ‘career’ as such. There is no scope for ‘promotion’ in a clerkship as there is in other jobs. Your pay and responsibilities remain the same irrespective of the number of years you spend in an office. Hence, people usually take it up as a short-term assignment. It is well known that out of these, most take up clerkships in the hopes of securing a recommendation letter that will help them pursue their Masters *cough cough*. However, a law clerk need not necessarily be someone looking for a stop-gap job whilst they apply for LL.M.s. It’s also a great opportunity for people looking for a break from the rigmarole of law firms/litigation, people who want to explore diverse areas of law before zeroing down on a particular field, or anyone who wants to see the ‘other side’ of how the Supreme Court functions.

It is important to bear in mind that the nature and volume of work differ from office to office. Some judges prefer long briefs; others want very concise notes. Some judges prefer not to delegate too much work to clerks. Even work timings vary largely. Some offices are as rigorous as Tier-1 law firms. I would strongly recommend that you intern with a judge or speak to a previous or current law clerk so that you know what kind of work will be expected of you, but more on that later.

What not to expect from a clerkship:

Let’s deal with the grey areas before the good areas. A lot of people who apply for a clerkship seem to be under the assumption that their work-load will consist entirely of Keshavnanda Bhartis and Navtej Johars. People, especially those who haven’t interned at the Supreme Court before, also bear the illusion that everyone who argues before the Court is a Seervai certified expert in constitutional law. If you have interned or worked at the Supreme Court, you would know that it is only a first among equals. The same problems of pendency, lawyers seeking adjournments on account of the fictional illness of some fictional relative which increases said pendency, frivolous litigation, bad lawyering, good lawyering to obfuscate an absolutely meritless case, etc., which one witnesses in other courts, exist at the SC.

Most importantly, you will not always be dealing with life-changing constitutional questions. In fact, what you will learn through clerking is that what we prioritise in law school debates is a very elitist conception of the actual legal problems which plague our population. We are trained to believe that we will be spending our life as Nani Palkhivalas and M.C. Setalvads, when actually your bread and butter is going to consist of demarcating the property boundaries of Raj Uncle’s Sector 16 flat and getting Simran Aunty her Provident Fund dues. At the SC, like in the lower courts, disputes are often won or lost on facts, and the sooner you understand that, the easier life as a clerk and as an advocate will be for you.

Additionally, as you may have figured out, a clerkship is mostly behind-the-scenes work. This is perhaps the reason why, unlike in the United States, clerkships are less-publicised and have relatively lower value in public perception as a career choice in India. A pet peeve of mine is that relatives, fellow members of the legal fraternity, and Tinder matches view clerking as a glorified internship. Things marginally improved when I acquired the hallowed SC ‘Proximity Card’. Even then, a common scene in the SC canteen is to have hapless clerks bullied into vacating their seats by ‘advocates’ or for a rebellious clerk to proudly flash their proxi-card and refuse to give up their seat. Ek chutki black gown aur white band ki keemat tum kya jaano, vakeel babu. (translation: one pinch of black gown and white band – how would you know its value, you lawyer *based on the famous dialogue from the iconic movie Om Shanti Om*)

Jokes apart, a clerkship should not be viewed as an easy ‘getaway’ job even though it involves a different set of tasks than those performed by litigating advocates and transactional lawyers. You are bound by the same, or perhaps a higher degree of confidentiality as you would be in a law firm or lawyer’s chambers. You are operating under constant deadlines to deliver briefs and notes, and there is no opportunity for seeking an adjournment or extension. There will be moments where you will have to brief the most frustrating and mind-numbingly boring/frivolous files. Most importantly, there is always going to be the pressure that if you don’t perform, you will be disappointing a constitutional functionary. Therefore, you are likely to encounter the same degree of challenges as you would in any other job. Just that everybody thinks you’re an intern, but you’ll get over it.

What you can take away from a clerkship:

A lot of people have asked me if working as a clerk helps if you are planning a career in litigation. In terms of hard skills, maybe not so much. You will be foregoing one year of seniority which you could have acquired in a law firm or chamber, and you will not be learning drafting work or court procedure such as filing, inspection, etc. However, you will definitely pick up a lot of soft skills[1] in terms of understanding what kind of argumentative style can be persuasive to judges (hint: the number of juniors flanking you is not influential), in what cases they are likely to (or not) interfere with lower court judgments, etc.

Secondly, clerks are exposed to a wide diversity of matters. We go through law school patting ourselves on the back for knowing the difference between formal and substantive equality under Article 14 or being able to rattle off provisions of the IBC. However, as mentioned earlier, when you actually go through case files, you will figure out how much what we perceive as ‘mundane’ or small-fry topics in law school, make up the bulk of litigation. Inter alia, land acquisition claims, builder-buyer disputes, motor vehicle accidents, labour disputes and insurance claims are more likely to occupy your time and headspace than fundamental rights jurisprudence. This is not to say that the academic work we do in law school is useless. Every now and then there will be some headlines-grabbing constitutional matter which will usually lead to you gasping for breath and basically not hearing anything as 20-odd clerks fight for precious courtroom space with you (fellow clerks will guess what I’m talking about). However, our prioritisation of what legal issues merit discussion is configured from a privileged space and often does not account for what ordinary litigants actually care about, so it’s good to get that reality check. It’s also fun researching on a wide variety of topics, especially special legislations, which you were hitherto unexposed to (If anyone ever wants legal advice on mutawallis, you can approach me).

A clerkship is also really useful for learning statutory interpretation, and how important it is to the legal profession. Irrespective of your CGPA or University Round Rank in law school, if you can’t tell your ejusdem generis from your noscitur a sociis, you aren’t really a legal scholar yet. A lot of times, a case turns on how to interpret one ambiguous word in some archaic rule more than the application of some mind-boggling legal theory.

The most important take away from clerking for me personally is that it helps you become vastly more open-minded and practical about how the law and legal adjudication works. As a clerk, you will often be required to put your personal biases aside while conducting research. This might prove a difficult task, given that most of us are prone to inhabiting ideological echo chambers. You are either conservative or liberal. Feminist or MRA. Lover or hater of the green fries at joint mess dinners. And so on and so forth. Of course, as law students we are also trained to play the devil’s advocate, look at the grey side, employ post-modernism, etc. but we vastly tend to frame our judgements of right and wrong in terms of some ideological paradigm. There is a tendency to think that in any legal dispute, there has to be a ‘good’ side and a ‘bad’ side and as a lawyer, it’s your duty to help the ‘good’ side (from your ideological perspective) win. However, when you assist a judge, you learn that the factors that influence the adjudication of a dispute are vastly more complex. Sometimes the facts say one thing, but a badly-drafted statute might say something else. Sometimes the law is on one party’s side, but the facts favour another. Doing justice in one case would set a slippery precedent for future cases.

Those who have studied feminist jurisprudence or feminist legal methods under Prof. Elizabeth may have come across a term called ‘positionality’. Positionality requires that you should be willing to critically examine your worldview and consider those of others, without necessarily compromising or surrendering your principles to them. I think a clerkship is the best way to understand positionality as a method of thinking in practice. This works both ways — being a clerk also gives you the opportunity to put your perspective across to judges and share the outlook of the current generation of lawyers with them. Contrary to what you might think, they are often more than willing to engage with opposing/novel ideas and appreciate it if you take initiative in bringing the latest legal debates or academic developments to their notice.

Applying for a clerkship.

Now to the part you all are really interested in — how do you get a clerkship? There are two ways of going about it. The first is to apply through the SC Registry, in which case you will have to give an exam and an interview. If you are selected in this, the Registry itself will assign you to a judge. The second is to send a personal application to the office of the particular judge(s) you wish to clerk with, which usually consists of a cover letter, CV, and a writing sample. For obvious reasons, the second method is more popular.

There is no uniform set of criteria that can determine your chances of getting a clerkship. Every office has their own preferences and requirements for clerks, depending upon the nature of work involved. The best way to go about applying, in my opinion, is to intern with a judge beforehand so that they have the opportunity to observe your work and evaluate your application accordingly. I personally did not have the foresight to do so, but from experience, I can say that many judges prefer persons who’ve interned with them previously. The second option is to take advantage of good old NLS nepotism and speak to alumni who are already clerking so that they guide you in the application process. Even if you don’t know any alumni, it is desirable that you generally speak to someone clerking at a particular office so that you have a realistic picture of what their judge expects from prospective applicants. Most offices finalise recruitment around March/April, so you should start laying the groundwork at the beginning of your final year of law school.

The biggest mistake that people make when applying for clerkships is that they base their expectations of the kind of work they will be doing and their interactions with the judge they will be clerking with based on what is reported in the media. Merely because a particular judge is hearing a high profile case or a case in your favourite area of law at the moment does not mean they will be hearing those kinds of cases on a daily basis. It is also important to keep in mind that there are no specialised ‘benches’ which exclusively deal with the death penalty, IPR, tax, etc. It is true that certain judges tend to deal more with ‘commercial’ or ‘social welfare’ matters etc. based on their area of expertise, but the most accurate way of gauging what matters a judge actually hears is the Judges’ Roster on the Supreme Court website. It is recommended that you check the Roster before applying, because that is going to be 99% of the subject matter of the work you do, irrespective of what you may know through hearsay.

Similarly, people often tend to presume that they know everything about a judge based on what they’ve read off Bar&Bench or social media. They may have their subjective reasons for the same, which are perfectly valid. However, the facets of a judge you get to see while working in their chambers is often in stark contrast to how you see them in court (which is something you’ll get to know after speaking to clerks). In my opinion, the most important part of a clerkship is not about deriving validation for having worked with an SC judge or having attended the hearings of a landmark case. These are experiences which can also be replicated with a Senior Advocate. It is mostly about what you can take away from your personal interaction with a judge. Your most important lessons during a clerkship are not going to be from the research you do for a judge, but from the little nuggets of wisdom they drop while discussing a case or recounting personal anecdotes. It’s not just that they know the law better than you; they also know a great deal more about life than you do. Therefore, don’t clerk merely because you want to put ‘Besties with XYZ judge’ on your CV/Insta or because you see yourself being part of some revolutionary judgement. Be sure before applying that you genuinely want to learn from the person you are applying to.

Conclusion

Sorry, this got a tad too long. ‘Briefly’ speaking about my own experience, I have genuinely had a great time in the past year (which is evident in the fact that I’m continuing). To be honest, there were moments of FOMO in the beginning when I wondered if I was following the right life trajectory and if I should have taken up a law firm job instead. However, ultimately I don’t have any regrets. For those concerned about financial planning, you won’t be rolling in money of course, but a clerkship pays enough to live reasonably in Delhi (unless you spend all your money on tandoori momos and Big Chill like a certain someone who is not me).

Of course, if you are absolutely sure that your goal in life is to become a Senior Advocate or become an equity partner, then I suppose there is no point in doing a clerkship. The reason why the clerkship worked for me was because I don’t come from a legal background and my litigation internships during law school had been quite shitty. I hadn’t even interned at the SC before. Doing a clerkship helped me get a reality check about how the Supreme Court actually functions. So for those who want to test the waters before plunging into the Dark Sea of litigation, a clerkship is a good preliminary option. A clerkship is also a great option for people who prefer a career in academia or policy to hone their research skills. To sum up: great research opportunities, good opportunity to observe a mix of both ordinary lit matters and high stakes constitutional drama, and a daily dose of Lutyens sightseeing (the India Gate circle panorama is going to be imprinted in my brain for the rest of my life).

That’s it from me folks. If you have any other queries, feel free to PM. Stay safe, and remember to wash your hands, you detty pigs.

_____________________________

[1] Just in case someone is wondering, no reference is intended to a recent batch group discussion.

]]>

When I was a child, my neighbour used to feed my brother and me whenever my parents went to the village. She would invite me home for food. I would sit on the floor; her entire family would sit at the table.

Bahujan scholar and poet Omprakash Valmiki described in his biography, his father’s insistence on him pursuing a higher education, despite knowing fully well of the discrimination that his son would inevitably face. A child who had already faced such discrimination from primary school, was hence burdened with the expectation of a higher education, with the belief that it was the only route to ridding himself of caste.

I am a Chamaar. This is not an identity that I have ever shied away from. While some of you would expect me to identify as a ‘human’ first, I want to assure you that the society at large has made sure that I don’t forget which caste I belong to. In my time at Law School, as I have gone from identifying as a Chamaar to identifying as a Dalit-Bahujan, I have always embraced the one part of my identity meant to keep me down. As I write today, however, I offer a small glimpse into a journey, familiar to some and incomprehensibly unfamiliar to others.

Much like Omprakash Valmiki, my parents too, harboured dreams of escaping caste. Escaping, however, comes at a price. The price of an education, was sacrificing a house. To send your son to the best possible school, you had to sacrifice the down payment that you could have made on a home. With each tier of education coming at a greater cost, the sacrifices would mount and my parents would make them; because at the heart of hearts they shared the same vision of Dr BR Ambedkar and Omprakash Valmiki. They (and I) genuinely believe that a higher education is the only avenue for one to rid themselves of caste.

I joined Law School in 2015 but my journey began 2 years prior, when I prepared and wrote the CLAT in 2014. Back then, I had gotten a score which would have seen me enter RMLNLU. Determined to improve and make it to the best possible Law School, I rewrote in 2015 and sat stunned as I checked my results at 2AM in the morning. I had secured an AIR of 333. I was dejected. I really thought I could have done better.

In the morning I rang up one of my closest teachers who had helped me with my preparation and informed him that I had gotten an AIR of 333. Being the supportive man that he is, he was delighted. He congratulated me on my effort and told me it was a result of my hard work. Almost as an afterthought, I informed him of my AIR SC Rank 2. He was ecstatic. He yelled in joy and said my entry into NLS was certain. Here is when I was caught in my first dilemma. I expressed to him my doubts about joining a college based on my SC Rank and instead simply accepting a college as per my General ranking. The words he said then fuel me to this day. He said “If you don’t go, the seat will be offered to a child who might not be able to bear that pressure and drop out. Remember, you don’t go there for yourself, you go there for your people; as a guiding light for those students who can look up to you and follow you in the same footsteps.”

Truth be told, these footsteps haven’t been easy. Each step through Law School has thrown up challenges reminiscent of the inequities that exist outside. But after an unlucky streak of two year losses, it is these words which prevent me from dropping out like so many other Dalit-Bahujans, and kindle my hope of graduating from this institution with all the knowledge that I came to gather.

The pursuit of knowledge here, however, seems particularly strange through the lens of a Dalit-Bahujan man. On a campus that boasts equality campaigners in all corners of its settlement, I continue to witness, with each new batch of students, similar incidents of caste-based slurs, “debates” on why “economic reservations are the solution” (this from those joining our LLM and MPP programs) and a culture of discrimination that only serves to remind individuals of their place in the socio-economic hierarchy.

When Valmiki’s father insisted on his pursuit of higher education, the forms of discrimination that he feared may have been different. But in the second decade of the 21st century one can be certain that the perpetrators, then and now, draw from the very same well. Incidents of discrimination, against an individual, only hasten the collective reliving of a community’s historical inferiority complex – of not speaking good enough English, of not being able to understand complex concepts in one go, of not “fitting in” to elite cliques, of not knowing how to compile presentable projects, of not clearing exams.

In the initial days of college, a group of students sitting in their hostel rooms were discussing the marks of the first test of Legal Methods. In the course of the conversation one of my batch mates very casually remarked “Yaar, yeh SC kaise aajate hain iss college mein?” (“Dude, how do these SCs come into this college?”). One hopes that the men present have changed their views over the years, however, the impact that one such statement has on its listeners can persist for years. After all, we were all just first years who wanted to hang out, but from that moment on we would always be reminded that in their eyes our existence would simply never measure up. One day you are a proud member of India’s premier law school, and the other you are just another Dalit who got in through reservation.

The way higher education is portrayed as a route to salvation, one often forgets that those they meet on this journey are a product of the same patriarchal, brahmanical caste-based society that exists outside. For all those who forget, however, incidents like these serve as a reminder.

When I came here, education was my primary aim. I started to participate in practice debates because I wanted to speak in English and make sense at the same time. I wanted to participate in class so I tried to contribute. Prof. Elizabeth (aka Lizzie) encouraged everyone to engage and debate in class. Even though the first 3 weeks of History were Latin to me, I started to relate heavily to the lecture on “Society and the Individual” from the “What is History” component. It was here when I first tried to speak in class a few times while seated at the back of the side rows, all the while anxious of being made fun of. Over time, I slowly gained in confidence and my engagement in class increased, till one fine day, I got stuck trying to formulate a sentence and a batchmate of mine looked at me and smirked. That was it. All that effort into building myself up, deflated. The said person later joined the Law and Society Committee. Little did I know that in my second year, I would face the same kind of deflation, only this time it would be at the hands of a Professor, who would use his privileged position, to mock me for the class’s entertainment.

Trust me. It breaks you. Being made fun of for struggling with a language you weren’t exposed to because your parents only spoke to you in either Bhojpuri or Hindi. It cuts at your self-esteem and stabs at your confidence. It effectively kills your sense of curiosity and robs you of your ability to participate. And yet. And yet, it doesn’t break you like you may think it does. It may break your heart, but it does not break your spine. One keeps marching forward towards that goal that is graduation, because one does not walk this path for the benefit of caste perpetrators but towards their direct detriment. Once again, one hopes these people have changed, but the fact that the said Professor continues his antics, doesn’t leave me feeling very optimistic. The certainty with which people say “Arey, people develop sense while they stay here” can only emerge from those unaware or intentionally blind to how deeply ingrained this mentality is in our institutions.

Academic achievers, and discourse creators keep discussing how caste-based discrimination has either vanished or radically reduced with the onset of education. As someone who studies at the premier centre for legal instruction in the country, I would like to categorically disagree. Caste discrimination has merely evolved into discrimination by other means. Language, clothing, taste in music or your consumption of pop culture, each act as a proxy for your socio-economic location. While the cliques that form around these may seem banal, they represent a much deeper divide.

When you enter they ask you your rank, and then look at you with pity. When you speak English they mock and they jeer. Little do they know that their “merit” is bought by money and their rank by a historic access to resources. Their spoken English reeks of condescension and their debates uplift none. Their pretence of inclusivity dies when they shoot down someone for speaking Hindi, and again, when their moot courts “groom” and “polish” the pre-polished selected for “grooming” and “polishing”.

The table from my childhood seems to have persisted to my present.

Distant. Intimidating. Unattainable.

The only difference is,

When I was a child, I ate on the floor.

I will sit on the floor no longer.

]]>For those of you who thought this would be a meta article based on my Marquez-esque title, you’re wrong. I just had to show off a little to begin with. Although I adore the author, the only people I currently identify with are Ross and Rachel, as quarantine forces me into a slowly decaying potato state of mind (and body) in the middle of my 10th rerun of this ghisa-pita hua show. For context, Ross is a cocky weirdo who likes Rachel, and Rachel, like a true Law School girl with no options, inevitably falls for him. Then they break up and make up and break up and make up and break up and make up (yes, I have put the exact number of times).

Why do I currently feel like them? Something is oddly familiar about the way they yell “We are SO over,” “We were on a break,” “I don’t need your stupid ship” and the like, only to fall in a limbo of uncertain feelings again and again. After all, I’ve had my own love-hate, on-off, toxic, full of incredible highs (hehe) and painful lows relationship over the last 5 years. This is not a romantic expose — I speak of Law School. And much like Rachel, only now that the ship has finally sailed, do I realise how much I will miss the stupid ship.

This ship has a lovely exterior, full of green and white and red, and it draws you into its fold immediately, like a beautiful green Venus fly-trap. The exterior of course conceals the air of anxiety, the unsteady ceiling of ridiculously high expectations, and the noxious environment of gossip and judgment that surrounds the entrant. Not to mention the institutionalised structural hierarchies and stigma that shape most interactions here. The bad times here are bad to say the least — but never fear because now we have not one but TWO counsellors (*orgasm*) to get us through it.

But perhaps my ship is more than just a well of cloying bitterness.

My ship is purple-orange skies that appear on cold evenings with the warmth of the laughter of your friends around you. My ship is evenings spent at Chetta doing the one leg dance (girls you get it) discussing anything from the CAA to the fond memories from a trip to Gokarna. My ship is the hungover smile on faces when they pass the newly muddy, brown Quad on mornings after a raging party. My ship is the genuine happiness on a beloved professor’s face when an entire batch surprises him one evening with a cake. My ship is the hours spent in exertion training batchmates to dance to Bollywood songs from 2 am the night before Eastern Dance.

My ship also has these tiny corners of light that I’ve often taken for granted. The pleasure (lol) of being woken up at 12 pm by loud, giggling ammas rather than your irate family screeching your name. The hours you spend talking about everything and nothing in your neighbour’s room, that you’ve made your own. The moment a professor exclaims in excitement because of a fierce but fulfilling academic fight in class. And most importantly – Atithi’s aloo parathas that can make any horrible day okay.

And CUT. Feel nostalgic? Yes, I do too. Now imagine someone throws you off this ship into the depths of the open sea with no warning. For context, watch Shah Rukh Khan throw Shilpa Shetty off a terrace in Baazigar in slow-mo (who wouldn’t?). The sea is cold, it is uncertain and you see no direction or relief. Yet you are expected to leave your beloved ship and home of several years, and begin to swim away from it. Except due to our friend Karuna, you can’t begin swimming away, and you’re immobilized in a position where your beloved ship is right there in front of you and you could have been on it, but it is now also beyond your reach.

People tell me this is adulting and this is the way of life, but as a good friend recently told me — yeh sab capitalist construct aka mohmaya hai. So, screw being mature about leaving Law School. We are going to whine and weep and prolong our stay when we come back for our luggage (lol sorry first years). Because this is our home.

This is not to say our experiences here are not shaped by who we are. As an upper caste cis-woman from a metropolitan city, I acknowledge my experiences are positive because of my privilege and background. Law School has a long way to go to make this ship a steady and joyful ride for more than just a few. Yet, Law School is also a people, and for them I am most grateful.

A Quirk article would be incomplete without gyaan, because Quirk articles are usually gyaan/ woke movie reviews/ cool rock sing-alongs no one gets, and we love it. My gyaan is simple – channel my batchmate Adit Munshi. Go back to college and take pictures of everything. Of trees and treadmills, of food and fungus, of Chetta coffee and class. Because believe us, it is heartbreaking to have no closure and a dream of OLTs that you thought you would get and memories you thought you would make. Treasure your time on this ship, because kal ho na ho, aur agar hoga bhi, toh bohot sucky hoga.

The fifth years shall continue our bingos and binge-watching, in the faint hopes that we can return to our beloved ship before that is lost to us forever. In the meantime, keep up the academic rigour and the scholastic incrementalism y’all!

]]>Hi Aman, tell us a little bit about your time in Law School. What committees were you a part of, what kind of activities were you interested in, and what did you prioritise?

For me, Law School was an opportunity to try everything that it had to offer, while also learning the law. Hence, I took possible experiences as checkboxes that I must tick before my time is done. To this end, mostly to keep myself amused, I played for multiple university sports teams; didn’t debate [the ones done for First Attempt Exams (FAs) don’t count] but ended up going to World’s Debate as an adjudicator; contributed to the moot trophy cabinet; took up a teaching assistantship; fought and, in a first, won against an SDGM fine on appeal.

I firmly believe that if you do not like something that you are stuck with, you mustn’t wait for someone else to fix it. I spent a large part of my Law School life in a quest to improve the collective student experience at NLS. There are three things that any NLS student whines about the most: a) Mess Food, b) Campus Infrastructure, and c) Academic Standards (Pre-Sudhir era I am told. No?). I was in a position to work on all of them as I was the Convenor of both the Mess Committee and the Campus Development Committee. I ran for the Student Bar Association (SBA) office based on that body of work. Through my time as SBA President, I am glad to have contributed to the creation of additional common spaces on campus- by seeing through the construction of the Navalgund Park [Country Club!] and the AIR Café, and by opening up the football field to persons of all genders. With the support of some terribly passionate friends, I ensured that NLS saw some long-overdue academic reform — electives — despite strong opposition from a big chunk of the faculty. It is something that I am particularly proud of.

Your time in Law School as described by you and perceived by others might make sense in hindsight – how one thing fell in place right after the other. But a lot of the times it is just about winging different scenarios as they come to you, and doing the best you possibly can, when faced with them.

You graduated from college about two years back, what’s your career path been like in these two years?

Well, it would look like quite a whirlwind, although, if you ask me, it has come a full circle. After Law School, I started my career in the insolvency team of Luthra and Luthra with the late Mr. Sameen Vyas (RIP). Almost half a year in, a tremendous opportunity came my way as an offer to join the campaign staff of Mr. Jyotiraditya Scindia for the Madhya Pradesh Vidhan Sabha and the subsequent Lok Sabha Elections. I grabbed it with both hands and it turned out to be a life-altering experience. Now it has been more than half a year since I returned to my hometown, Bilaspur, in Chhattisgarh, to practice law.

Why did you leave your corporate law job? Was choosing an alternative career, especially one in politics, a difficult choice to make?

The choice of a career in politics wasn’t difficult at all for me. I have tremendous interest in the Indian polity. Politics is the most intellectually stimulating and challenging arena. There are no set rules on how to go about your business. When I was in Law School, I had interned with the Opposition Chief Whip of a Legislative Assembly. After Law School, I also had an offer from Prashant Kishor’s political consultancy, IPAC. I didn’t take it up because one doesn’t know what project one would be assigned, and my involvement in the elections would possibly have been remote and indirect. So I held out until an opportunity enticing enough to take the plunge came my way.

Such opportunities are extremely rare because there exists what I call a ‘Gatekeeper Syndrome’ in political spaces. This is where the insiders try to throttle the entry of outsiders as they are perceived as a threat to their proximity to the source of power. I think I was lucky that Mr. Scindia had a vibrant office of talented and secure young professionals. My friend, Bhuvanyaa Vijay, who had joined it as a LAMP fellow, held the door for me, as she wanted to discontinue.

As for leaving my monetarily lucrative job, I had become certain that a career in corporate law was not where my interests lay. There were two primary factors that helped me come to this conclusion. First, there was a significant gap between my work output and the eventual outcome, resulting in minimal job satisfaction. My team was doing perhaps the most cutting edge work in insolvency law practice at the time, representing a mammoth client for a huge NPA bid, and setting precedents for subsequent practice. One fine evening, the resolution plan that we had prepared for months got accepted and I got congratulatory messages from many people in the firm, but I really didn’t feel any joy or even a sigh of relief. It was that day that I knew for sure that I wanted out. Second, I personally enjoy the public domain and regular interaction with people from all walks, creating value for them by offering solutions. A law firm wasn’t conducive to this, for me.

What are the demands of a job in politics?

In public life, one’s life is one’s work. Your value, while working for a mass leader, comes from how much of his time you can help him save – when everyone is vying for a piece of that time. This is more so in an election year where he is responsible for his own seat as well as the campaign management of a state entrusted to him by the party.

In such a situation, you are pretty much required to be a generalist — from analysing seats for ticket allotment, designing a campaign for his own seat and overseeing the implementation on the ground while working with local political actors right down to the booth level (which I believe was the most tricky part) to writing his speeches and handling media houses/ journalists as well as social media.

Most of the times you will basically find yourself saying “Yes Sir, I’ll figure it out” and then doing whatever it takes to get the job done. To this end, I also ended up spending more than three months traversing through each and every corner of the Guna parliamentary constituency in Madhya Pradesh.

Do you think your education at Law School helped you with the job? Do you feel like your stint as the SBA President helped in anyway?

I am very grateful for my Law School education. It teaches you how to ask the right questions, how to be articulate, how to frame an argument, and a whole bunch more. That the traditional legal services industry is the only beneficiary of our learning is really quite tragic. It came in very handy for the parliamentary work. Even otherwise, it makes you more aware, sensitive, and perceptive, all of which is essential for a generalist.

With respect to my SBA experience, to get to office, you have to run a campaign. So, there was some experience, but I must admit we are talking about a gargantuan difference in scale and demography (this doesn’t fully capture it). People skills are a big plus. Moreover, NLS did not have any social media handles until my tenure when we started them. I used to personally run the Facebook page for both my own and Mathew’s term and make all the posts. That experience turned out to be useful when handling Mr. Scindia’s accounts and other PR with news agencies, both digital and print.

What was the best part of your job in politics? Could you share some interesting stints from your time?

I must tell you it’s a job full of adrenaline rush. Some of the best bits (that I can share!) include being in the AICC War Room on the counting day for legislative elections with the entire MP A-team including Mr. Scindia, Kamal Nath, Digvijaya Singh, Vivek Tankha et al, and just being glued to the TV and EC website for 14 straight hours. I kid you not, it was so tight throughout that none of us ate anything all day, until after midnight when it was certain that the INC is forming the government. A similar rush was on the voting day for Guna Lok Sabha where I was running a 50 people monitoring room for 2200 polling booths in real-time, and troubleshooting any election misdeeds that were being reported by our polling agents.

The common perception is that politics is a dirty business, which could act as a deterrent. What do you think about this?

Politics is a difficult business. The premise of it is based on pushing an incumbent out of power or retaining power despite the opposition. Some say it’s either your goons or mine. Just kidding. But I am hopeful for a generational shift in politics, for it to go from a quest to acquire power to the discharge of public service. For that to happen, you need good people to constantly engage with the political establishment.

Politics, if done right, has immense potential for good work. For instance, I was spearheading a water project in Shivpuri (Guna) which was supposed to connect a dam, with a 30 Km water pipeline, to the city suffering from acute water scarcity. I was to work and coordinate with the local governing body (Nagar Palika), the Collectorate, and various other departments of the state government. The project was incomplete for the last eleven years but within four months, we ensured that water from the dam reached the Shivpuri city. It was a lesson on what ‘political will’ can do where I witnessed how a congenial government committed to the cause can propel and give direction to the administration to fix what isn’t working. Unfortunately, after the Guna election loss, I couldn’t follow up. Further, and sadly, I recently found out that the intra-city distribution network, which was supposed to be completed sometime last year is broadly still where I left it off last year and the people of Shivpuri will still have to bear with the vagaries of supply through water tankers this summer.

What made you choose to go back to a career in law after one in politics?

I took a plunge but I always knew I wanted to do it only till the end of the Lok Sabha elections. It is the biggest democratic exercise in the world and I was fortunate that I was only 23 then. The next one would be in 2024 and I would be too far down the road in my career to break away from it. So if I had to do it, then 2019 was the perfect time.

Ever since my first year in Law School, I’ve always wanted to go back to my home state and practice law. A growing state needs good and competent lawyers and more importantly, its people to return and work for it. It is indeed difficult in the face of an entire generation having moved out of the state elsewhere. The practice of law by its very nature also offers wide-ranging opportunities to be working in an intersection with politics. So I do look forward to all the exciting opportunities ahead of me and wish to be a part of the growth story of the state.

What would be your piece of advice to someone looking to explore a career in politics?

The concept of political staff/ campaign staff hasn’t truly evolved in India unlike what you see in US teledramas. The political offices are usually run by long time aides who have been with the leader for years, if not decades, because they understand the pulse of the constituency and, most importantly, the relationship of the leader with his people and the local party organisation. There are limited avenues for young professionals or students freshly out of institutes to join a political office directly. Apart from the Gatekeeper Syndrome, it also remains an underpaid job and there isn’t any set career trajectory. Hence, it’s a risky proposition.

There are many ways of doing it. First, there are instances where young professionals permanently join the office of a high political functionary, for instance, that of Mr. Rahul Gandhi and some others that I know. It has the potential to provide a long-term career trajectory within the party organization. You could also start working for a prominent leader at your home state and see how it works at the grassroots, pick up useful insights, understand state political dynamics and take it from there. I can’t map it out generally as it is one uniquely long road which will take many turns depending upon the ever-evolving political environment and that’s perhaps the beauty of it. Second, is through the LAMP where people join an MP allotted by PRS, with the scope of work limited to the parliament. The main issue is that you have no say in the allotment. Third, is joining the research team of ministries of the Government which hire professionals on contract. Fourth, is to join a political consultancy, which is contracted by parties for different state elections and can also offer stability and a career trajectory.

All said, I recommend that if politics interests you, you should at least get a taste of how an election in India is fought and chew on a big chunk of responsibility. If so, timing is everything and you must try and get on the campaign staff of a prominent leader. Take it from me, there’s always more work to be done than there are hands on deck, and your brush with the ground realities will be of immense experiential learning.

When I had left my corporate job to join Mr. Scindia’s office, I was thoroughly apprehensive about what is in store. As I look back, I feel extremely glad that I did take the plunge.

]]>This piece has been written by Manisha Arya (Batch of 2019). You can reach out to her at [email protected]. Artwork by Mukta Joshi (Batch of 2019).

“I now see how owning our story and loving ourselves through that process is the bravest thing that we will ever do.”

– Brene Brown

When I say ‘upper class’, do not mistake me to be born with that privilege. My father, having been born and brought up in a village, is the first-generation graduate of our family. I was born in a village, shifted to a town, and later shifted to a city in 2005, where I lived for 9 years before coming to NLS. Moving to a city was a conscious decision made by my father so that his children could get a proper English education. My father’s several promotions in his government job are what gave us the ‘upper class’ social standing. This is the background I come from. So, the next time you want to comment about Bahujans that “they have an iPhone, they do not deserve reservation” (glorious mess table conversations), remember the struggles our forefathers have gone through to give us a comfortable life. If you can afford an iPhone, so can we. Make peace with it.

Beginning of Law School

I was CLAT General Category AIR 639 and SC AIR 2. I entered NLS having no knowledge about what it meant to be from the SC category. I was not even aware about what being a woman means, leave alone an SC woman. Yet, I felt this constant guilt, a constant feeling of not deserving what I got. I was SC AIR 2, I should have been proud of myself, but I was not. This feeling of not deserving to be here deepened when I got three repeats in my first trimester itself. Eco was expected; History, I thought I would clear in the repeat; and LM, I was sure I would pass. Failing in 3 out of 4 subjects hit me so hard that I broke down, I felt like I would not survive. After much hesitation, I went to Prof. Elizabeth in my second trimester and told her how I felt about being from a reservation category and about my academic struggles. One hour of conversation with her helped me take one step ahead in feeling like I deserved to be at NLS.

No matter whether one fails or excels in academics, the stigma attached to one’s caste never leaves you. If you fail, you were bound to because you came via reservation. If you excel, you excel despite your reservation. The stigma attached to one being from reservation never goes away. Like an author once said, “you can leave your caste but your caste will never leave you.”

Friend Circle

Luckily, my friend circle was a mix of Bahujans and Savarnas and my friends never otherized me because of my caste. I say ‘luckily’ because not all Bahujans have the fortune to say the sentence I just said. We are all aware, even if we chose to ignore it, about the formation of friend circles based on caste, or committees taking people from their own caste and taking pride in being an all <insert caste> committee. In such a surrounding, I am extremely grateful for having the friends I did, and will always be thankful to them for making my Law School journey a path of roses even when it was full of thorns.

Mentorship – or the Lack of it

The importance of mentorship in Law School can only be understood by someone who did not receive it. Unlike many other students, I did not get a mentor in the form of a rank parent, got no guidance on how to go about college, had no one to proof read my projects – no one to provide the support which could have made my journey a bit easier. I am not the only reservation student who has faced this problem, it is a vicious cycle, where the category students are so caught up in their own academics that they often do not have the time and energy to invest in another student.

Savarna students often have strong rank families, which helps them make strong connections both in Law School and in the professional world. We Bahujans are often lost as to where to get internships from, under whom to intern, how to go about in the profession after our graduation, and so on. I do not say that seniors will not help us if we ask for it but what is served on a platter to the Savarna students, the Bahujans have to fight for. How much of this is the student body’s fault and how much of it is the institution’s is a long going tussle.

The journey of Owning my Identity

Learning about my identity as a woman and as a Bahujan  was a journey — a process. My first encounter with caste was in my second year in the History II course when we were reading Uma Chakravarti’s ‘Rewriting History’. My second academic encounter was in 2017 when Prof. Sumit Baudh offered an elective on ‘Critical Race Theory and Caste’.

was a journey — a process. My first encounter with caste was in my second year in the History II course when we were reading Uma Chakravarti’s ‘Rewriting History’. My second academic encounter was in 2017 when Prof. Sumit Baudh offered an elective on ‘Critical Race Theory and Caste’.

2015-16 was the time when Savitri Phule Ambedkar Caravan (SPAC) was being formed and emerging as a committee working for caste rights at Law School. As far as I remember, I got involved with the initiative in 2016. By being in SPAC and engaging with fellow Bahujans I started understanding the spirit of community, the need to be there for each other, and the necessity to not let our juniors go through the things we experienced. In my third year, I started seeing myself as a Bahujan not with guilt, but with pride.

In 2016, LawSoc conducted ‘The Indian Apartheid – A Conference on Caste’ where I spoke on the themes of changing one’s surname to hide one’s Dalit identity, the discrimination faced, and the impact of division of caste into sub castes on Dalit Women. That was the first time I realised that the journey of Bahujan women is not the same as that of Bahujan men. This realisation became a reality in 2017, when I was made joint-convenor of SPAC and on multiple occasions my views contradicted with those of the Bahujan men in SPAC.

In 2016, a Bahujan man committed a sexual offence against a Savarna woman in law school. The Internal Complaints Committee gave an order convicting the perpetrator. Appealing against the order, the perpetrator misused the process of law, revealed the identity of the woman, and made many derogatory remarks on her character – going to the extent of making her responsible for the suicide of one of my batchmates. The authorities he approached were not authorities who could pass orders in such matters. All evidence was against the perpetrator – there was documentary proof of him abusing the process. With all of this, the woman approached SPAC to support her, so that she could get a final conviction against him. Most men in SPAC (especially the Convenor of that year, 2017-18) did not support her — even with all of this proof, they did not want to step up. They feared that NCSC (National Commission for Schedule Castes) would come after SPAC. To be honest, they were just cowards.

SPAC had a close association with one of the Bahujan alumni of the Batch of 2014. A batchmate of mine had shared with me the experience of her emotional and sexual abuse perpetrated by him and requested that SPAC stop associating with the alumnus. I discussed the same with the SPAC Convenor. In return, he defended the senior by stating ‘the fair process of law – audi alterem partem’ and no action was taken. In 2018, multiple testimonies of sexual abuse against the alumnus were published. After so many attempts at discussions and fights, I understood the misogyny of these men and that strengthened the feminist inside me.

It is an ongoing trend in SPAC and in the Bahujan community at NLS that the women are not vocal, they do not speak up, they do not fight. Why? I still ask. Later, at Strawberry Fields-2019, the aforementioned 2017-18 SPAC Convenor sexually harassed three Bahujan women and we came to know that the same thing happened with all three of us only after discussing it – one spoke first and then the other two. That’s the importance of sharing our stories – if we had not discussed it, most probably none of us would have confronted him. I do not know why I did not call him out in public back then. I just do not know! He was a friend of mine, an ally, a person I often looked up to — and then he turned out to be a harasser.

Corporate Internships and Placement

In my third year when Corp internships began and it was time to think of placements for the next year, my CGPA was 3.08. When I saw my CGPA and my class rank, my confidence took a steep drop. I was convinced that I would not get a Corporate internship. I did not want to do a corporate job – this I was sure about – but this was also an excuse I made to not sit for placements. In reality, I was shit scared and extremely under-confident because of my CGPA. I just could not muster the courage to sit for placement with a CGPA of 3.08. After graduating however, I deeply regretted stealing myself of the opportunity of learning from the experience of sitting for interviews which could have helped me later in job interviews that I actually wanted to sit for. Take this piece of advice, no matter what your CGPA is, do not give up without trying, do not reject yourself, because someone else might not.

Mental Health

I suffered from severe anxiety and depression throughout Law School. A lot of it was because of my past, but the academic pressure and the feeling that I did not deserve to be at NLS also contributed to it. As a Bahujan, I always wanted to excel in academics, so that no one could question my merit – the pressure was immense. As a woman I wanted to be at my best in committees, be at my top game in sports, I never ever wanted to hear that “she lost because she is a woman” or “she could not perform because she is a woman”. I remember exerting myself so much more than the men of the committees that I was a part of, or choosing work of infra – lifting more than men would, even when I knew that I was physically exerting myself. I just did not want someone, any man, to say “she cannot lift mattress/tables/tie ropes/carry a hundred things at one go because she is a woman”. I know for sure many women at NLS feel the same.

Two of my batchmates ended their lives, and both of them belonged to the reservation category. I hesitate to write about it as the struggles they suffered in their minds can only be known to them. However, what I would like to discuss is the academic pressure that they were going through before they decided to take that step. One of them, due to their illness, had to leave mid-trimester and when they came back in the next trimester, they had to hustle with the Exam Department for attendance, beg again and again to schedule their vivas – they were afraid of losing the year because of this. The other one just needed one or two marks to clear a subject which could have saved their one year, and the institution just declined to do so, being well aware of their illness.

Do one or two marks or a year matter to the institution more than someone’s life? Could a little sympathy on the part of the Exam Department and the institution have saved their lives? Both of them were bright, they had so much potential in them, they could have contributed so much to the legal profession and society at large. But, sorry, we need to keep up the name of the institution, we need to keep up the academic rigor. If a few lives are gone, especially the lives of Bahujans, what does it matter?

On another note, to all the students I want to say it gets better, it always gets better. Do not give up on yourself, because your friends and your family will not. You matter the most, above grades, above a degree, above this fucking, sorry, glorious Law School, YOU MATTER THE MOST.

Concluding Note

Law School is the place where I first heard of Ambedkar, Savitiri Bai Phule, Jyotiba Phule and read their works. Law School is the place where I first owned my caste identity and spoke openly about it. I would like to extend my heart-felt gratitude towards Prof. Elizabeth and Prof. Sumit Baudh for teaching me these subjects and for the manner in which they taught. They have been my friends and my mentors, for that I am always thankful. Law School is the place which gave me the courage and the confidence to be who I am and be proud of it and for that I owe Law School a lot.

Parting my ways with Law School as a student, I am sad to find out that only 5 category students out of 17 (excluding the person who was a sexual offender) who came to Law School in 2014 graduated with the batch. Eight have a year loss or year losses, two students dropped out, and two we lost.

In Solidarity,

Manisha Arya.

*Disclaimer — the description/information of the sexual harassment case has been shared with the permission of the complainant and has been proof read by her.

]]>

Hi Apurva, thanks for taking out time for this interview. Can you start by telling us a little bit about your time in Law School? What committees were you a part of, what kind of activities were you interested in, and what did you prioritise?

So, I had a fairly humdrum Law School life, which is to say I did most of the usual stuff. In most things, like sports, academics, mooting and debating, I was painfully okay. So I carved my own path in some ways and did not partake much in committee-life.

In my third year, I co-started a humour and satire email account called Jitenge.bhi.Jitenge. This account used to send these ludicrous emails to my batch to drum up interest in our sporting events, but over time, it grew to be much larger than that. Some of the things we did with it were quite bold. Once we wrote to the VC to bless our mid-law party and allow us to take a cement duck from his lawn to be our party mascot. A lot of random things like that, but our humour in those emails was always top-notch. This innocent experiment was my first brush of doing something new and very unique to me in Law School.

Towards the end of college, I had a big desire to give back. It’s hard to state here how much Law School changed me. I came in as a cocky guy who was greatly insecure about most things beneath the surface. Law School beat up my ego well and, in the process, made me more humble and self-aware, which explains my desire to give back. So, in my final year, I stood for the position of Vice President of the SBA and co-started Quirk. As a result, my final year of college was my most busy and challenging year of all of my five years at Law School.

As a whole, I think I prioritised activities that lead to my own self-development. I felt that the student experience of Law School was very sub-optimal and undertook initiatives to improve that. It was this desire to improve Law School’s communal aspects that led me to prioritize Jitenge.bhi, SBA and Quirk.

It’s now been four years since you graduated Law School. What have you been doing since then?

Immediately post-Law School, I worked in the Consumer & Retail investment banking team at Deutsche Bank (DB). This was in Hong Kong and Mumbai. I worked there for a bit over 1.5 years, after which moved to FSG, a social impact consulting firm in Mumbai. I spent exactly 2 years there, and since February 2020, I have been on a break from work till I go to business and design school.

Was choosing an alternative career a difficult choice to make, given the importance of corporate law jobs especially around 4th year in Law School?

This is a hard question to answer. In some ways, it was a straight forward choice because the opportunities in law were not appealing to me. But yeah, what was challenging was the uncertainty of trudging down an uncharted track. In hindsight, it seems silly. Doing an IB analyst role is maybe one of the most well-defined career paths out there.

One of the options in law that I did consider was to litigate. I felt a draw towards both its entrepreneurial and intellectual sides. I had also, foolishly, romanticised the hustle involved in litigation. After I had done a stellar internship in the Bombay High Court in my third year, I began to seriously consider it, but there were some grave doubts in my mind. First, I was unsure if I wanted to spend decades of my life in just one city. The second was that I did not know if I loved law enough to sustain interest to grind it out for years. And the third, the most practical one, was that I did not know how to financially sustain myself in the early years. Being reliant on my parents was not appealing.

With these doubts, I felt I should still give corporate law a chance. So I ended up doing a two-week internship at a big law firm. That experience was sufficient for me to know that it was definitely not meant for me. I was not put off by work or the hours per se, but more by the unhappiness and unprofessionalism I saw around me. Everyone was always walking on eggshells, teams did not seem to be collaborative with one another, interns were given the most mindless work, hiring was nepotistic etc. Everyone was decently remunerated, but the lifestyle and culture were not appealing.

Soon afterwards, DB came to take interns and thankfully they picked me. Later they gave me a full-time role and that marked the end of my career in law. After this, I never considered going back to the law except for one time, towards the end of my time at DB, when I gave an interview with a very senior person at a kickass law firm. After they awarded me an offer, I immediately knew I had made a mistake and retracted my application with profuse apologies.

How do you feel about not working with the law per se, which is a concern many people in Law School have about alternative careers?

Oh, I love not being involved in the law. It has probably been the best decision I’ve made to date. I had grown exceptionally disillusioned with the teaching and practice of law by my fourth year, especially how it eschewed any form of legal empiricism. And once you get disenchanted like that, it’s hard to recover.

I think all those who wish to explore alternative careers should know that staying in the law is far more straightforward than hustling outside it. Being from NLS, you enjoy unparalleled privilege. Even inside law firms, NLS folks have more visibility with the decision-makers. So breaking away from the law does puncture this privilege significantly. Mind you, I am not saying that a career in law is by any means easy, far from it in fact. All I’m saying is that it’s predictable. But once, you get over that fear, you realize that predictability was a silly notion to hold dear.

On a more abstract note, breaking away from the law did open up the world and its wonders to me in profound ways. Surrounded by highly smart folks with backgrounds in engineering, economics, business etc., was the best bit. There is much to be learnt from these different schools of thinking.

What are the demands of a job as an investment banking analyst? What about as a consultant? Do you think your education at law school has helped you with the job?

The analyst role is an old and well-greased way to step into investment banking. In this role, you are under the tutelage of senior bankers, where you assist them in either completing corporate transactions or seeking new business. Unlike law firms, here you get involved early into the transaction process because a part of your role is to originate transactions i.e. go to a CEO and propose a potential M&A etc. It’s a great role with a steep learning curve.

As a consultant, your subject matter is vastly different. While you are still in the business of selling services, the kind of business problems you solve differs dramatically. Here you pitch to solve an operational or strategic issue faced by a client. As a result, you generally experience a variety of projects of different types (unlike transactions in investment banking, which differ significantly in terms of nuances but are still financial problems).

I worked in FSG, a social impact consulting firm, where we primarily helped the government, philanthropic foundations and corporations invest their capital in ways that led to the most beneficial impact. The ‘Law, Poverty and Development’ course taught by Ms Neha Mishra was a big influence on my moving to FSG and wanting to blend business realism and social impact. Some of my projects at FSG included helping scale a for-profit education company that served low-income primary schools in urban India, designing toys that children in low-income households could use to learn fundamentals of math and English from the concept of play, help shape global sanitation policy by understanding what made some sanitation businesses more profitable than others etc. Interesting work overall.

In most junior roles, the expectations are the same. People want you to take ownership, ask smart questions, have an eye for detail, show a good attitude etc. They call these things basic hygiene. Though law school did not prepare me for the technicals of any job, it did help me be decent at these aspects. However, it was never the classroom instruction or the projects that helped me here. It was all the learning I experienced in leadership roles.

What is the best / worst part of these careers?

Hmm, this is another tricky question to answer because the best/worst is so subjective to the specific role and individual. The best bit about junior roles outside the law is the steep learning curve of new skills and ways of thinking. What I mean by this is that law school is great at teaching you how to either make or defend an argument. What it glosses over is how to make an on-ground change. And this is what most businesses are about.

So for example, even our projects are intellectual exercises. For any topic, we consult the various legislations, explore the debates behind their drafting, deep dive into opinions and judgments of courts and study prior academic thought. All of this is done with an agenda to look at an existing issue from, hopefully, a new unexplored academic angle. But all the while, there is little thought on how to change the issue, on how to mobilize action, on how to create sustainable models that actually change things on the ground!

So back to my point, the careers outside the law, especially in business, are centered around a different way of thinking. They involve attacking an issue with an attitude of ‘how can we solve it’, as opposed to ‘how can we study it’. Also, careers outside the law also allow for more freedom to manoeuvre around and assume greater leadership roles early in the career.

What would be your piece of advice to someone looking to explore a career in these areas?

Network, network, network. Finding what you want and then breaking in is the hard bit. So try many things, learn some marketable skills, speak to many people and get a host of experiences. Most people want to help university students, so reach out! You’ll be surprised at how generous people are with their time. I am also happy to be contacted using this link.

The other thing I suggest is to decide early if you want to break away from the law. If you’re in fourth or fifth year with a modest inkling that you may not enjoy working in a law firm, try doing an internship in something else to test the waters. There is so much happening in Bangalore right now. It’s harder to discover alternate career options 2-3 years into a law firm job if you haven’t already allowed yourself the freedom to explore what you like.